Feminale 23

Belinda Cadbury

Judith P. Fischer

Marie-France Goerens

Ingeborg G. Pluhar

Andrea Pernegr

Veronika Rodenberg

Tonneke Sengers

Irene Wölfl

exhibition: June 16th - September 12th, 2023

opening words by Katrin Bucher Trantow - Chief Curator, Deputy Director Kunsthaus Graz / A

opening words by Katrin Bucher Trantow - Chief Curator, Deputy Director Kunsthaus Graz / A

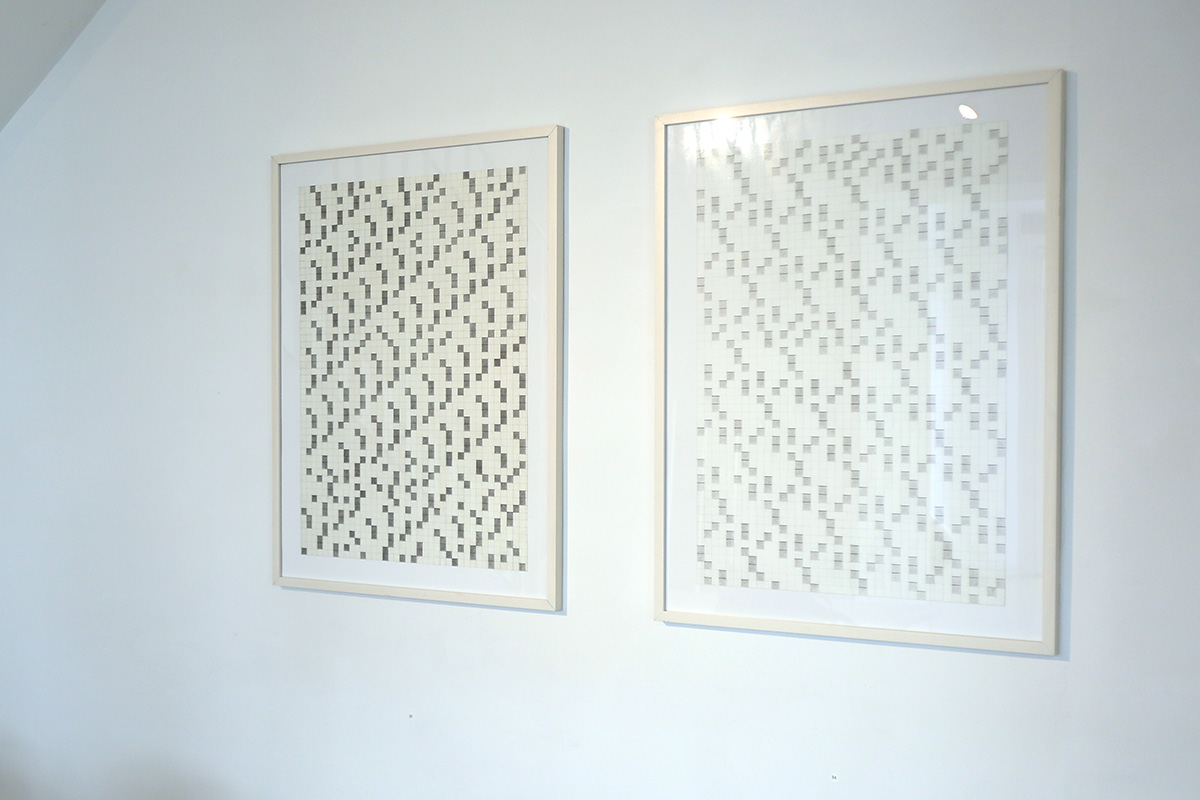

Feminale 23 presents eight international contemporary positions of visual artists of different generations in dialogue with each other. The works shown have something in common: they give sensuality, value and permanence to apparent trivialities, forgotten or found or used materials, patterns mutating in rhythm, geometric interpretations of space or compositions mathematically reduced to a minimum.

Judith P. Fischer is primarily about irritation. With the cushion we associate softness and security, sleep and devotion, care and care. The cushions from the series PILLOWTALK, however, are not soft at all, but hard and rigid, as if frozen. Some of them were further processed by drawing, covered with fine pencil strokes, which makes the surface even more textured, emphasizes the heights and depths of the form. This is a synthesis of object and drawing. And ultimately drawings hang on the wall. For the drawing usually stands at the beginning of all artistic sculptural considerations.

In the collage series "Empty Finds," Ingeborg G. Pluhar dealt with things advertised in glossy magazines of the 1970s. Or rather with the trappings of these things. Advertising pages with a staged everyday object, which she carefully cut out. And it is precisely the omission of the actual protagonist that makes the everyday thing enigmatically interesting. On the other hand, and this is even more important to her, she elevates her empty inventions, the remaining surrounding space, such as the shadows, to the actual star of the former glossy page.

Andrea Pernegr also devotes herself to the accessories of daily use, to the intimacy of the personal environment, in a very expressive abstract language that is also affectionately devoted to these things. She also pays respect to trivialities in her light-hearted expression. Simple, everyday objects or situations of her garden in central Burgenland she paints to oases of joy and freedom. She underscores her delight in this environment by repeatedly supplementing her paintings with glyphs, thus finding a very individual form of expression of writing and abstracted symbolism.

Marie-France Goerens' works are based on a dialogue between "good and bad" form, perfection and inaccuracy, realism and abstraction. She uses her materials, often collected remnants of various painting grounds, either as models or integrates them as fragments of reality in her installations. In the works of her new series "WORK THE CANVAS" she composes various, subtly and at the same time daringly coordinated canvas remnants into virtuously composed textile collages. Here the canvas is not merely a carrier material for color, but the primed or pure canvas surface with its fringes and threads of tears and cuts is the determining element itself. By picking up remnants and reusing them appreciatively in her creative processes, she creates composed order.

"Poems" is what Irene Wölfl calls her new series, in which she makes texts of old book pages the main protagonist of her works. Irene Wölfl always uses what she calls "found objects" in all her series. Discarded packaging material, forgotten memories in attics, or fabric remnants whose heyday is long past. In the "Poems" series, too, such materials, which are laden with stories, form the framework, the environment for the selected page of text. Irene Wölfl's intervention is, as always, far-reaching, for she erases most of the lines of text by painting over them. What remains are new texts with new content. A trademark of her method of representation is drawing with a sewing machine. Seams of varying thread thickness and color give the many superimposed layers of past times support and graphic pointed performance.

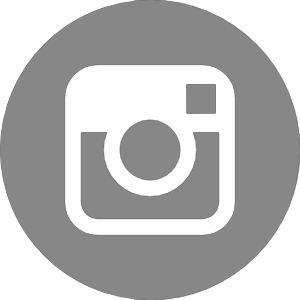

Just as everyday objects, painting materials, or found objects from the past can be sources of inspiration, even materials for new interpretations, when the all too present takes on a new value in this exhibition, the works of British artist Belinda Cadbury expand the sustainable access for the ubiquitous in a somewhat different way. Belinda Cadbury buzzes geometric concrete patterns, gray values on drawing paper. Patterns are grids characterized by infinite repetition. Not so with Belinda Cadbury, however, as she breaks the monotony with unexpected changes of rhythm, their shades of gray causing unconscious irritation, attention, and tension. Like a steady, recurring melody, from time to time pleasantly enriched by subtle foreign harmonies in the familiar listening scheme.

Another facet of presenting the familiar in such a way that it becomes an unfamiliar new experience is demonstrated by Dutch artist Tonneke Sengers. She shapes two-dimensional geometry, rhythms that hover somewhat in front of the wall, into architectural spatial illusions. She cuts the constructions of the oblique-cracked building elements out of wooden panels or aluminum panels, whereby the omissions with their shadows on the wall behind them convey an additional facet of three-dimensionality. In doing so, she strives for objectivity, for clarity and logic, from which an aspect atypical of minimalism is generated: individuality. And it is precisely this individuality that makes her works outstanding in a quiet way.

The German artist Veronika Rodenberg processes in her minimalisms the claim to the black square. A zero point in art history, which in Veronika Rodenberg's work is given an expanded interpretation through division and color accent. Her square minimalisms are more than a square, are fascinating spatial illusions with few picture planes. Her paintings are abstract spaces that open a window into infinity with few elements. Each composition is subject to a logical principle. Veronika Rodenberg's Purisms are not solely condensed rationality, rather they are highlights of mathematical harmony full of emotional quality.

Judith P. Fischer is primarily about irritation. With the cushion we associate softness and security, sleep and devotion, care and care. The cushions from the series PILLOWTALK, however, are not soft at all, but hard and rigid, as if frozen. Some of them were further processed by drawing, covered with fine pencil strokes, which makes the surface even more textured, emphasizes the heights and depths of the form. This is a synthesis of object and drawing. And ultimately drawings hang on the wall. For the drawing usually stands at the beginning of all artistic sculptural considerations.

In the collage series "Empty Finds," Ingeborg G. Pluhar dealt with things advertised in glossy magazines of the 1970s. Or rather with the trappings of these things. Advertising pages with a staged everyday object, which she carefully cut out. And it is precisely the omission of the actual protagonist that makes the everyday thing enigmatically interesting. On the other hand, and this is even more important to her, she elevates her empty inventions, the remaining surrounding space, such as the shadows, to the actual star of the former glossy page.

Andrea Pernegr also devotes herself to the accessories of daily use, to the intimacy of the personal environment, in a very expressive abstract language that is also affectionately devoted to these things. She also pays respect to trivialities in her light-hearted expression. Simple, everyday objects or situations of her garden in central Burgenland she paints to oases of joy and freedom. She underscores her delight in this environment by repeatedly supplementing her paintings with glyphs, thus finding a very individual form of expression of writing and abstracted symbolism.

Marie-France Goerens' works are based on a dialogue between "good and bad" form, perfection and inaccuracy, realism and abstraction. She uses her materials, often collected remnants of various painting grounds, either as models or integrates them as fragments of reality in her installations. In the works of her new series "WORK THE CANVAS" she composes various, subtly and at the same time daringly coordinated canvas remnants into virtuously composed textile collages. Here the canvas is not merely a carrier material for color, but the primed or pure canvas surface with its fringes and threads of tears and cuts is the determining element itself. By picking up remnants and reusing them appreciatively in her creative processes, she creates composed order.

"Poems" is what Irene Wölfl calls her new series, in which she makes texts of old book pages the main protagonist of her works. Irene Wölfl always uses what she calls "found objects" in all her series. Discarded packaging material, forgotten memories in attics, or fabric remnants whose heyday is long past. In the "Poems" series, too, such materials, which are laden with stories, form the framework, the environment for the selected page of text. Irene Wölfl's intervention is, as always, far-reaching, for she erases most of the lines of text by painting over them. What remains are new texts with new content. A trademark of her method of representation is drawing with a sewing machine. Seams of varying thread thickness and color give the many superimposed layers of past times support and graphic pointed performance.

Just as everyday objects, painting materials, or found objects from the past can be sources of inspiration, even materials for new interpretations, when the all too present takes on a new value in this exhibition, the works of British artist Belinda Cadbury expand the sustainable access for the ubiquitous in a somewhat different way. Belinda Cadbury buzzes geometric concrete patterns, gray values on drawing paper. Patterns are grids characterized by infinite repetition. Not so with Belinda Cadbury, however, as she breaks the monotony with unexpected changes of rhythm, their shades of gray causing unconscious irritation, attention, and tension. Like a steady, recurring melody, from time to time pleasantly enriched by subtle foreign harmonies in the familiar listening scheme.

Another facet of presenting the familiar in such a way that it becomes an unfamiliar new experience is demonstrated by Dutch artist Tonneke Sengers. She shapes two-dimensional geometry, rhythms that hover somewhat in front of the wall, into architectural spatial illusions. She cuts the constructions of the oblique-cracked building elements out of wooden panels or aluminum panels, whereby the omissions with their shadows on the wall behind them convey an additional facet of three-dimensionality. In doing so, she strives for objectivity, for clarity and logic, from which an aspect atypical of minimalism is generated: individuality. And it is precisely this individuality that makes her works outstanding in a quiet way.

The German artist Veronika Rodenberg processes in her minimalisms the claim to the black square. A zero point in art history, which in Veronika Rodenberg's work is given an expanded interpretation through division and color accent. Her square minimalisms are more than a square, are fascinating spatial illusions with few picture planes. Her paintings are abstract spaces that open a window into infinity with few elements. Each composition is subject to a logical principle. Veronika Rodenberg's Purisms are not solely condensed rationality, rather they are highlights of mathematical harmony full of emotional quality.